Home → Fish & Wildlife → Wildlife → Species Information → Birds → Seabirds

Seabirds

Photo Credit: Brad Allen

What is a Seabird?

Seabirds are colonial nesting waterbirds including Leach’s Storm Petrel, Great Cormorant, Double-crested Cormorant, Laughing Gull, Herring Gull, Great Black-backed Gull, Common Tern, Arctic Tern, Roseate Tern, Razorbill, Black Guillemot, Atlantic Puffin, and Common Eider (although eiders are waterfowl, technically not a seabird, they nest on islands with the seabirds).

What is a Seabird Nesting Island?

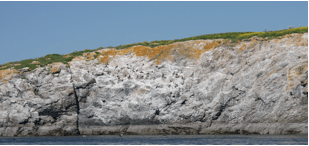

Worldwide, seabirds and certain waterfowl commonly nest on islands. Maine’s assemblage of colonial waterbirds utilize a wide range of habitats for nesting. There are between 3,000 and 4,000 islands and ledges off the coast of Maine. Prior to the last ice age, these exposed features were actually the tops of ancient mountains. While the forested islands are easy to count, discrepancy in the island numbers results for a combination of either counting each ledge independently or lumping ledge complexes as one, or including small ledges with the nearby island.

Many islands consist only of bare rock and are devoid of soil and vegetation. Approximately 1,700 are vegetated islands, ranging in size from less than one acre to Maine's largest island, Mount Desert Island. Spruce and fir are the dominant tree species on the larger islands. The smaller islands with the grass/forb/shrub vegetative component receive the greatest use by nesting seabirds.

Because of this wide variability, a comprehensive discussion of nesting habitat for this group is difficult. For instance, cormorants will nest in trees on islands, therefore forested sites are preferred. Maine has hundreds of forested islands, but very few are used by colonial waterbirds. Leach’s storm-petrels require soil conditions suitable for burrowing on offshore islands. Black guillemots need rock crevices and Razorbills a cliff ledge, common features on the Maine coast, but, in order to be suitable for nesting birds these sites must be relatively disturbance-free, particularly from predators. Many of the other colonial waterbirds that nest in Maine require dense grassy or brushy islands. Today, approximately 500 islands are used by nesting seabirds and common eiders along the Maine coast.

Photo Credit: Brad Allen

What is the status of seabirds in Maine?

Maine’s islands provide nesting space for these 13 species whose population status, distribution, and nesting habitat needs vary greatly. Some species occur in relative abundance on numerous coastal islands (Common eiders, Great Black-backed and Herring Gulls, and Double-crested Cormorants), and, for the most part, these populations appear healthy. Populations of Common, Arctic, and Roseate Terns had experienced declines since the 1930s and have recently begun to improve due to management programs and habitat protection. The other six species using coastal islands include Atlantic Puffins, Razorbills, Black Guillemots, Leach’s Storm-petrels, Great Cormorants, and Laughing Gulls. Populations of these birds, at the edge of their population ranges in North America, may be secure, but each require unique management and long-term population monitoring.

Photo Credit: Steve Agius

Why are seabirds important?

MDIFW is responsible for the stewardship of the State’s wildlife resources. Maine’s vast coast line and natural diversity, the challenge of sustaining these populations and habitats is daunting. Fish and Wildlife play an important role in the lives of Maine people. Maine’s fish and wildlife related recreation contributes over a billion dollars to Maine’s economy annually. The most obvious examples of this are the tens of thousands who annually join puffin cruises and the large number of waterfowl hunters who travel to Maine to hunt common eiders, as few spots in the country have this resource. Maine’s quality of life and its economy are by the diversity and abundance of fish and wildlife that inhabit our state. Several of the seabird species noted here are nesting at their ranges southern terminus. Others are nesting at their northern limit.

Photo Credit: Brad Allen

Nesting Island Ownership and Long-tern Habitat Protection

Approximately 70% of Maine’s nesting seabirds and common eiders now nest on islands owned by public and private conservation agencies. Individuals from and represented by these agencies and groups deserve much praise for their wisdom and efforts in protecting these special places for all of us to enjoy in the future.

In addition, seabirds nesting on several privately-owned islands have benefitted from the generosity of landowners who have donated or sold their islands to conservation groups or have conferred conservation easements on their properties. Lastly, because seabird nesting islands have been designated by the Legislature as resources of state significance under the Natural Resources Protection Act, nesting seabirds and their habitat receive additional protection into the future.

Regulations and Regulatory Authority

Prior to the 20th century, comprehensive laws to protect birds nesting on Maine's coastal islands were nonexistent. Today, protection and management of the migratory bird resource in the United States is provided by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 and subsequent amendments, authorizing the implementation of the various Conventions. The above agreements prohibited hunting of many birds, described which birds could be hunted, limited hunting to fall and winter, and prohibited market hunting.

Other agencies have contributed to the protection of seabird and eider habitat in Maine. The Maine Land Use Regulation Commission (LURC) administers land use planning and zoning responsibilities for areas without local government, and thus has regulatory authority over land use planning, zoning, and development activities on a number of eider nesting islands. In its Comprehensive Plan and Section 10.16,C of its Land Use Districts and Standards, LURC gives special consideration to seabirds (including eiders) nesting islands considered essential to the maintenance of seabird populations, as determined by MDIFW.

In addition, the Legislature of 1974 directed the State Planning Office to develop an official Register of Critical Areas. The Act defined Critical Areas as natural features of statewide importance because of their unusual natural, scenic, scientific, or historical significance. In 1976, 49 islands, which provided breeding habitat for 60 percent of Maine’s eider population, met the criteria for determining significant nesting areas for this species. The Critical Areas program no longer exists today (2000).

Photo Credit: Brad Allen

Seabird nesting islands are defined in IFW rules (Chapter 10.02F) as follows:

- An island, or portion thereof in tidal waters that has documentation of 25 or more: nests or seabirds, adult seabirds displaced from nests, or in combination (single species or aggregate of different species) in any nesting season during, or since, 1976; provided that the island, ledge, or potion thereof continues to have suitable nesting habitat.

- An island, ledge, or portion thereof in tidal waters that has documentation of 1 or more nests of a seabird that is endangered or threatened species in any year during, or since, 1976 provided that the island, ledge, or portion thereof, continues to have suitable nesting habitat.

Currently, 234 seabird nesting islands in organized townships with 25 or more nesting seabirds, are protected (by the permit review process) as Significant Wildlife Habitat under the Natural Resources Protection Act in Maine.

Twenty-one Roseate Tern nesting islands are mapped and designated as Essential Habitat under the Maine Endangered Species Act.

What are the Threats to Maine Seabirds?

In general, loss of food resources, catastrophic weather, habitat degradation, pollution away from the nesting islands, avian and mammalian predation, competition, shooting, oil spills and human disturbance may limit seabird populations.

Summary

Seabirds and common eiders gather in groups to nest on roughly 10% of Maine’s coastal islands. These populations experienced drastic population declines in the 1800s when island human populations peaked and island resources were exploited. However, by the beginning of the 20th century, laws were passed to stop the exploitative use of these birds.

Fortunately, most of Maine’s seabird and eider populations responded well to protection, habitat acquisition, and management in the twentieth century. Of the species that occur in relative abundance, current populations are projected to be stable over the next 15 years. Species that have experienced declines are receiving management activities aimed to halt the decline and improve future nesting populations and habitat conditions.