Home → Fish & Wildlife → Fisheries → Species Information → Arctic Charr

Arctic Charr

Common Name: Landlocked Arctic Charr

Other Names: Arctic Charr, Blueback Trout, Sunapee Trout

Scientific Name: Salvelinus alpinus oquassa

Origin: Native

Adult Size: Arctic Charr in Maine can live up to 15 years and attain a size of about 20 inches and 3 pounds. More often Arctic charr are much smaller; in some lakes the average size is closer to 6 inches and a few ounces in weight. A fish larger than 2 pounds is of significant size.

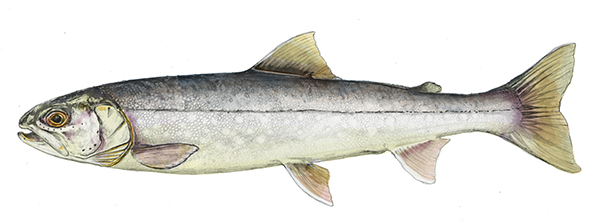

Identification: The Arctic charr is a slender member of the salmon and trout family. Usually dark on the back, lighter on the belly, and having light spots on the sides. Paired fins are orange to red with a bright white leading edge. Tail is moderately forked. During breeding season, both sexes become highly colored. Coloration can then range from pink to orange bellies, blue to brown backs, and creamy to orange spots. Fin colors can also become very intense during spawning.

Diet: Arctic charr are considered predators but have a broad-ranging diet. Prey may be taken from the water surface, down through the water column, and at the bottom of lakes and ponds. Fish are also consumed. It is common for Arctic charr populations to develop adaptations to feeding on a given prey item in a lake or pond.

Fishing Tips: Arctic charr are coldwater fish that prefer water temperatures less than 55 degrees Fahrenheit but will tolerate warmer water for short periods to take advantage of abundant prey.

After ice out in the spring, Arctic charr may be found anywhere in the water column due to uniformly cold water. As spring progresses to early summer, charr will make feeding forays into shallow water or surface waters to feed on hatching insects or small fish. Trolling small fish patterns is a common fishing method for charr at this time and lures need only be fished a few feet from the surface. Fly anglers will also find success at this time casting insect patterns on or just under the surface.

From July to mid-September, Arctic charr will be found in deeper water where temperature and oxygen are sufficient for survival. They often make daily movements up in the water column to feed on zooplankton, insects, and small fish, but rarely will reach the warmest surface waters. At this time of year, charr will be found at the thermocline (the water zone of rapidly decreasing water temperature) and deeper; this zone varies from water to water but is generally 20-30 feet. Trolling patterns in deep water is the most effective and some anglers elect to “plug fish” with lures, worms, or dead baitfish.

The latter part of September can be a great time to fish for Arctic charr. Depending on weather patterns, surface waters may have cooled enough to allow fish to move about the water column after a long summer period of dwelling in deep water. Arctic charr sometimes are seen feeding on insects on the surface mostly in the evening hours up until dusk. The successful angler at this time of year may be awarded with an adult fish in spawning colors.

Interesting Facts:

- Arctic charr are the northern-most fish in the world, sometimes living in lakes and ponds with no other fish, and where the ice doesn’t break from the lake every year

- Arctic charr across much of their range are found higher up in elevation and in deeper water than any other fish; in one Norway lake a charr was recently found living at 1,475 feet

- Charr commonly display polymorphism, meaning that 2 or more morphs, or distinct types, occur in the same lake. The different types feed on different prey, reproduce in different habitats and at different times of the year, and often are of very different size.

Management and Conservation: Arctic charr in Maine represent a unique resource represented by the only intact native populations in the lower forty-eight states. Furthermore, recent genetic work shows that Maine’s populations are genetically isolated, representing unique gene pools, and that many of them have adapted specifically to the available food base. For these reasons, MDIFW focuses on management that warrants protection for each individual population.

Several populations of charr have been extirpated in New England over the last 115 years, perhaps most notably in Maine’s Rangeley lakes region. Arctic charr in Maine were found first in the Rangeley lakes and were called blueback trout at the time; in fact, the subspecies designation, oquassa, originated from the lake with the same name (Oquassoc Lake was later renamed Rangeley Lake). Mooselookmeguntic Lake, Cupsuptic Lake, Richardson Lake, and Rangeley Lake had such heavy spawning runs in certain tributaries that protection under law was deemed unnecessary. Overfishing on these spawning runs and invasive species eventually took their toll on the population. By 1899 (when the first law was passed banning any take) the population had already collapsed. Today charr exist and naturally reproduce in 14 lakes and ponds of Maine including two populations established through translocation (the live transfer of fish) by MDIFW.

Today’s management of Arctic charr in Maine is guided by goals and objectives formulated and developed by a periodic planning process. Some of the guiding principles are use of conservative fishery regulations, protecting quality habitat, and conserving the unique gene pool present in Maine. Maine’s management philosophy is a conservative one toward the species; that is, maintaining and conserving each population is a high priority. Sport fishery regulations that adequately protect the species from overharvest, excessive hooking mortality, and the accidental or unauthorized introductions of new fish species are in place on all Arctic charr waters in Maine. Invasive species and the cumulative impacts of watershed use remain a serious threat for these populations.