Home → Fish & Wildlife → Wildlife → Living with Wildlife → How to Avoid or Resolve a Wildlife Conflict → Bats

Bats

On this page:

- Facts About Maine's Bats

- White-nose Fungus Disease Found in Maine

- Viewing Maine's Bats

- Bats in Winter

- Bats Houses

- Preventing Conflicts

- Public Health Concerns

- Legal Status

- Additional Information

Overview

Figure 1: Photo Credit - Ty Smedes

Bats are highly beneficial to people, and the advantages of having them around far outweigh any problems you might have with them. As predators of night-flying insects (including mosquitoes!), bats play a role in preserving the natural balance of your property and neighborhood.

Although swallows and other bird species consume large numbers of flying insects, they generally feed only in daylight. When night falls, bats take over. A nursing female little brown bat, for example, may consume her body weight in insects each night during the summer.

Contrary to some widely held views, bats are not blind and do not become entangled in peoples' hair. If a bat comes close to your head, it's probably because it is hunting insects that have been attracted by your body heat. Less than one bat in twenty thousand has rabies, and no bats in Maine feed on blood.

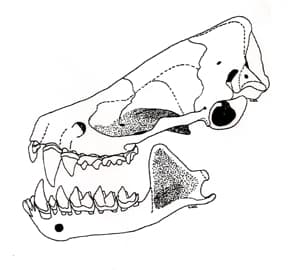

Figure 2: Drawing Credit - ODFW

More than eight species of bats live in Maine, from the common big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus) to the less common silver-haired bat (Lasionycteris noctivagans) and red bat (Laiurus borealis).

Bats range in length from the two-and-a-half-inch long Eastern pipistrelle (Pipistrellus subflavus), to the six-inch long hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus). The hoary bat has a body approximately the size of a house sparrow and a wingspan of 17 inches.

The species most often seen flying around human habitation include the little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) and big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus, Fig. 1).

Bats are the only true flying mammals. They belong to the mammalian order Chiroptera, which means "hand-wing." The bones in a bat's wing work like those of the human arm and hand (Fig. 2), but bat finger bones are greatly elongated and connected by a double membrane of skin to form the wing.

Facts about Maine's Bats

Figure 3: Drawing Credit - ODIFW

Food and Feeding Behavior

- Maine bat species eat vast quantities of night-flying insects, including moths, beetles, mosquitoes, and flies.

- Most bats hunt in flight or hang from a perch and wait for a passing insect to fly or walk within range.

- Bats primarily rely on a radar system known as echolocation to locate prey. The bat emits high-pitched sound waves that strike an insect and then bounce back. The bat interprets the reflected sounds to locate the prey.

- When flying, a bat often scoops insects into its tail or wing membranes, then transfers the insects to its mouth (Fig. 3). This habit results in the erratic flight that people see when they observe bats feeding in the evening.

- Bats will fly from half a mile to six miles from their roost to a feeding site, using temporary roost sites there until returning to their main roost.

Bats often capture insects when flying by scooping them into their tail or wing membranes, and then putting the insects into their mouth.

Hibernation Sites

- To cope with winter conditions, most bats use a hibernation site called a hibernaculum. (See "Bats in Winter")

- Hibernation sites include cavities in large trees, caves, mine shafts, tunnels, old wells, and attics.

- The hibernaculum protects bats from predators, light, noise, and other disturbances. Temperatures in the hibernaculum must be cool enough to allow bats to maintain a low body temperature but not freeze; humidity must be high and constant enough to prevent bats from dehydrating.

- Bats hibernate alone or in groups, and enter hibernation sites in late September or October.

- Maine only has a few winter hibernacula.

Nursery Sites

- Most of Maine's bats breed in early fall or winter at their hibernation site. Females store sperm until the following spring, when fertilization takes place after they rouse from hibernation.

- Most bat species produce one pup in May, June, or July; the specific dates depend on the species, locality, and weather.

- The young, called pups, are born and raised in nursery colonies occupied only by breeding females and their young. (Males roost alone or in small groups during this time, leaving the warm roosts and optimal feeding grounds for females)

- Females often use attics as nursery sites because these areas maintain the warm temperatures, from 85 to 104 degrees F, needed for raising young. The heat speeds the development of the fetus before birth and growth of pups after birth.

- In the nursery, the young remain with their mothers and suckle frequently. Pups are unable to fly for about a month, so the mother leaves her pup behind when she hunts.

- It is important not to disturb a maternity colony in the spring, when flightless young are present. Panicked females may abandon their young or drop them to their deaths.

- Female bats may return to the exact place of their birth year after year.

Mortality and Longevity

- Bats have few predators. Hawks, owls, house cats, and raccoons occasionally prey upon them.

- Natural events including long winters and fierce storms during migration can kill bats.

- Human activities, including habitat alteration, commercial pesticide use, control practices, and wind power development, are a major cause of mortality. Bats can die from direct exposure to pesticides or by eating sprayed insects.

- For their size, bats are the world's longest-lived mammals. According to records, one big brown bat lived in the wild for 19 years, and a little brown bat reached the age of 33.

White-nose Fungus Disease Found in Maine Bats

In February 2006, some 40 miles west of Albany, N.Y., a caver photographed hibernating bats with an unusual white substance on their muzzles. He also noticed several dead bats.

The following winter, biologists at the New York Department of Environmental Conservation received reports of several hundred dead bats in several caves, bats that showed erratic behavior, and bats with white noses. The biologists documented white-nose syndrome in January 2007.

Biologists have since found sick, dying, and dead bats in unprecedented numbers in and around caves and mines from Virginia to New Hampshire. In some hibernaculum, 90 to 100 percent of the bats have died. By 2010, the disease had spread as far west as Oklahoma and killed more than a million bats.

While they are in the hibernaculum, affected bats often have a white fungus on their muzzles and other parts of their bodies. In 2009, scientists identified the fungus Geomyces destructans as the causative agent of the disease. White-nose syndrome causes hibernating bats to awaken more often during hibernation and prematurely use up fat reserves needed to survive the winter.

Surveys for White-nose Syndrome conducted at hibernacula in Maine in 2009 and 2010 found no evidence of the fungus. Unfortunately during 2011 surveys, MDIFW biologists found bats at two sites in Oxford County with visible signs of White-nose syndrome fungus on their wings and muzzles.

Viewing Maine's Bats

The safest way to view and enjoy bats is to watch them in action. Bats are fascinating flyers, zigging and zagging about as they chase and eat insects. Little brown bats and Eastern Pipistrelle hunt over water. Big brown bats are often seen hunting along the margins of wooded areas, or silhouetted against the lighter sky as they twist and turn high above the tree canopy.

It's also fun to watch bats drink, which they usually do first thing after leaving their day roost. They scoop up mouthfuls of water with their lower jaws as they fly over lakes, streams, ponds, or water troughs. Most bats do not come out to eat or drink in heavy rain or when the air temperature remains below 50 degrees F.

To View Bats, Follow These Tips:

- The best places to see bats in flight are places where night-flying insects abound, such as next to a stream, lake, or pond; over a meadow or large lawn; along a forest edge; or around bright street or porch lights.

- Choose a warm summer evening and a site where bats have been spotted flying, or a known roost site from which they will emerge, such as an attic or bat house. Remain still and quiet; and listen for the squeaks or clicks that many bats make before emerging.

- Some species of bats begin their night flights 20 to 30 minutes before dark. The common big brown bat may be out foraging earlier. Other species don't emerge until after dark.

- With the aid of an inexpensive commercial bat detector, listen for the echolocation calls bats make when navigating and locating prey.

Bats in Winter

With few to no flying insects available to them during winter in Maine, bats survive by hibernating, migrating to regions where insects are available, or a combination of these strategies.

During hibernation, metabolic activities are greatly reduced. A bat's normal body temperature of around 100 degrees F is reduced to just one or two degrees higher than that of the hibernaculum, and the heart rate slows to only one beat every four or five seconds. A hibernating bat can thus survive on only a few grams of stored fat during the five- to six-month hibernation period.

Banding studies indicate that little brown bats will migrate 120 miles between hibernacula and summer roosts, and, if undisturbed, they occupy the same site year after year. They select areas in the hibernaculum where there is high humidity (70 to 95 percent), and the temperature is 34 to 41 degrees F. Still, there are some species, such as the big brown bat, that can hibernate in relatively exposed situations in buildings where there is considerable fluctuation in temperature. Hibernation lasts until April or early May.

It is important not to disturb hibernating (or roosting) bats. If a bat rouses early from hibernation, it must use its fat reserves to increase its body temperature. A single disturbance probably costs a bat as much energy as it would normally expend in two to three weeks of hibernation. If disturbed multiple times, hibernating bats may starve to death before spring.

Because some bats hibernate in buildings during the winter months, bat-proof a building only when you are sure no bats are hibernating in it. If bats are found hibernating inside after October 15, they should be left alone until early spring (prior to the birthing period in May) after the weather has warmed enough for insects to be out regularly. Meanwhile, seal all potential entry points into human living spaces, and develop a plan so the exclusion process can be accomplished effectively in spring (see "Bats Roosting in Buildings").

Bat Houses

- Some bat species prefer man-made structures to their natural roosts, whereas others are forced to roost in buildings when natural roosts, such as caves and hollow trees, are destroyed.

- The little brown bat and the big brown bat frequently use bat houses. A well-designed, well-constructed, and properly located bat house may attract these and other species.

If you are making a bat house to use in Maine, paint it with multiple coats of flat black exterior latex and place it where it will receive full sun. Maine bats need and seek a home that bakes in the sun – a nice warm place to raise their young – and one that lets them decrease their metabolic needs during roosting.

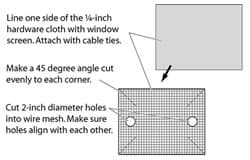

Build or buy a bat house that is at least two feet tall and 14 or more inches wide. Bigger is better. A roughened or screen-covered landing platform measuring three to six inches should extend below the house.

The house can be single-chambered or multi-chambered, but chambers should be three quarters to one inch wide; including variety in size will provide for the needs of different species.

The houses should be caulked during construction and (preferably) screwed rather than nailed. The idea is to create a tight microclimate inside the house, one capable of trapping both the heat of the day and the warmth generated by the bats themselves.

Place the house in full sun, preferably on its own pole; the next-best location is on the southern side of a building in full sun. The optimal temperature range is between 85 and 104 degrees F. Do not put it on a tree, which provides too much shade and is too close to hawk and owl perch sites. Keep the area around the entrance clear of obstructions for 20 feet.

Don't worry that adding a bat house to your property will encourage bats to move into your attic or wall space. If bats liked your attic or wall spaces, they would probably be living there already.

(See "Additional Information and Resources" for more information about bat house design, placement, and maintenance.)

Preventing Conflicts

For some people bats don't present a problem. For others, bats can be a worry, especially when they become unwanted guests in an attic, inside a wall, or in living space.

Unlike rodents, bats have only small teeth for eating insects, so they do not gnaw holes in walls, shred material for nests, chew electrical wiring, or cause structural damage to buildings. Bats therefore cause minimal damage, but they can be noisy and alarming, and the smell of bats and their droppings can be offensive. It is possible to learn to coexist with bats and to benefit from their presence.

If a conflict arises, first make sure bats are the cause by observing the following:

Bat droppings: Bats defecate before entering buildings and places where they roost. In buildings where there is an attic roost or a roost in a wall, an accumulation of droppings may fall through cracks and stain ceilings and walls. Insects associated with bat droppings rarely bother humans.

Droppings are usually the size of a grain of rice, crumble easily between the fingers, and contain shiny, undigested bits of insects. The droppings of mice are much harder and more fibrous.

Bat sounds: Bats often squeak before leaving their roost at night, and may chatter on hot days when they move around seeking refuge from the heat. Baby bats separated from their mothers will squeak continuously. All these sounds are loud enough to be heard from a distance of up to thirty feet. Thus, an increase in such noises near dusk probably indicates bats.

Rats, mice, flying squirrels, opossums, or raccoons – rather than bats – may be causing scrambling, scratching, and thumping sounds in attics and walls at night. Swifts (birds similar to swallows) can in rare instances make chirping and rustling sounds in a chimney at night.

Bat odors: Bats produce a musky solution from their scent glands and their roosts may take on a strong musky odor. Areas occupied by rats and mice also often have a musky smell.

Figure 4: Drawing Credit - Land Mammals of Oregon

Side view of a big brown bat skull (See Fig. 4) Unlike rodents, bats do not gnaw holes in walls, shred material for nests, chew electrical wiring, or cause structural damage to buildings.

How to Exclude Bats Roosting in Buildings

Like other wild animals, bats will seek shelter in an attic, wall, chimney, or other suitable area. Bats are able to squeeze through surprisingly narrow slits and cracks; the smaller species need only a half-inch opening. Sometimes when homeowners discover bats in the attic, they feel that they have a crisis that needs immediate attention. In fact, they may have been coexisting with the bats for many years.

Trapping and relocating bats is not recommended. Traps can be fatal to bats if left unattended and can quickly become overcrowded. In addition, bats have excellent homing instincts and, when released, they may simply return to the capture area.

Prior to excluding bats, consider partitioning bats off from the area where they are in conflict with humans, and allowing them to roost elsewhere in the structure. An effective partition can be made from construction grade plastic sheeting and wooden battens. Another consideration is to provide an alternate roost site, such as a properly designed and installed bat house mounted close to one of their exits. Install the bat house before excluding the bats as described below.

The best way to get rid of bats, and also the safest for bats and humans, is to exclude them. However, because old buildings offer many points of entry – as do buildings with shake or cedar shingle roofs with no underlayment -- it may be impossible to exclude them completely. You can hire a wildlife damage control company experienced in excluding bats or you can do the work yourself. In attics and areas where large numbers of bats have been roosting for years, it is safer to hire a professional to do the work (including the cleanup of accumulated droppings) than to do it yourself.

Note: Never trap flightless young or adult bats inside a structure; this is needlessly cruel to the bats inside and can create a serious odor problem (see Bats in the Winter for important information about when not to exclude bats).

To Exclude Bats From Most Structures:

Option A – Build bats out:

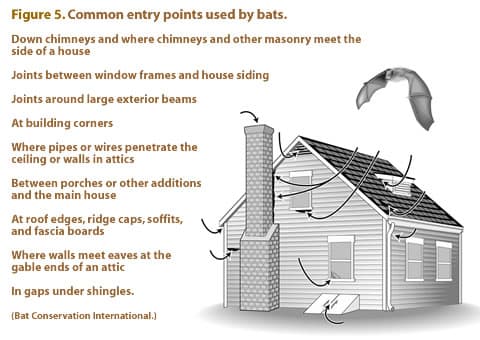

From mid-October to mid-March, when bats should still be hibernating, or after you have made sure no bats are roosting in the attic or other area, seal all potential entry holes (see Fig. 5). If possible, enter the attic during the day and look for light shining through cracks and holes. Insert pieces of fiberglass insulation or bits of stick in these holes to mark them for repair from the outside.

Seal off large openings with aluminum flashing, wood, or quarter-inch mesh hardware cloth. Stuff small holes around pipes, cracks, and gaps in shakes and tiles with balled-up galvanized window screening, pieces of fiberglass insulation, copper Stuff-it®, or copper or stainless-steel mesh scouring pads. (Steel wool will corrode quickly after becoming wet). Use weather-stripping, caulk, or expandable foam, seal spaces around doors, windows, and vents. Replace loose boards and roofing materials. Close the damper in the fireplace.

If you use caulk or expandable foam, apply it early in the day so that it is set up and no longer sticky when bats inspect the area in the evening. If there are large areas to be foamed, it may be worth purchasing a foam gun of the type used in building construction. Foam is very messy to use, so wear gloves when applying it, and don't get it on your clothes or skin.

Figure 5: Drawing Credit - BCI

Common entry points used by bats: Down chimneys and where chimneys and other masonry meet the side of a house; joints between window frames and house siding; joints around large exterior beams; at building corners; where pipes or wires penetrate the ceiling or walls in attics; between porches or other additions and the main house; at roof edges, ridge caps, soffits, and fascia boards; where walls meet eaves at the gable ends of an attic; in gaps under shingles.

The advantage of caulk over foam is that it comes in a variety of colors and it is easier to apply. Before purchasing, check the label to make sure the caulk can be painted.

Insulation blown into wall spaces may be an effective barrier, but it must be done when bats are absent to avoid trapping them in the fill.

If bats are present, holes can also be blocked over a period of days early in the evening after the bats have left the structure to feed. Do this only from mid-August to mid-October (after the young bats have learned to fly and before cold weather arrives). Another window of opportunity occurs in early spring, before the birthing period in May.

For several days, bat counts should be made as holes are closed, leaving the main exit open. On the night of the final count after the bats have left, the main hole should be plugged to prevent their reentry. The following evening, remove the plug to allow any remaining bats to leave before you seal the exit.

Option B – Harassment:

If bats must be excluded, persuade them to move to one of their alternate roost sites by creating an undesirable atmosphere. Again, there are two windows of opportunity: from mid-August to mid-October, after the young bats have learned to fly and before cold weather arrives; and in early spring, before the birthing period in May.

Bats don't like to roost in areas with bright, windy, or noisy conditions. Therefore, locate the area where bats are roosting and light the area with a bright light, such as a mechanic's drop-light or trouble light, located away from burnable objects. (Use a fluorescent light to save on electricity and keep the heat level down) In addition, aim a fan and a loud radio at the bats. Begin the harassment process shortly before dark and keep it in place day and night. Because bats may move to a dark, protected area, you may need to move the lights and other equipment, or install them in various areas. Putting up sheets of plastic to separate the bats from the rest of the area can be effective, but make sure you don't block the bats' exit or exits.

Commercially available ultrasonic devices may be effective if they are placed in a small, confined area with roosting bats. Bats can hear high frequency sounds; these devices, inaudible to humans, supposedly bombard the bat's range with jackhammer-like noise.

Do not use naphthalene flakes or mothballs, which contain chemicals that can be toxic to humans and other life forms; poisoned bats may fall to the ground where they die slowly and are more likely to come into contact with children or pets.

If the exclusion process was successful, immediately seal up the exits to prevent bats from reentering. If necessary, install a chimney cover, available from home improvement centers.

Option C – Install exclusion devices:

Again, from mid-August to mid-October (after the young bats have learned to fly and before cold weather arrives), or in early spring (before the birthing period in May), identify the exit(s) bats are using. Have friends or family members stationed at the corners of the structure after sunset on a warm calm night. They need to be far enough away to see as much of the building as possible without having to turn their heads; it takes only a second for a bat to exit and take flight. Observers should note from which side of the house – and, on subsequent nights, exactly where – bats exit the structure. Remember that the hole can be as small as half an inch.

Bats often defecate when exiting and reentering a building, so look closely for rice-sized black droppings clinging to the side of the structure. If you see droppings, you will find the exit hole directly above it. (To make sure droppings are new, remove existing droppings or lay down newspaper over them to see if more appear) Bat body oils may also discolor a well-used opening.

Seal all entry holes but one using the methods described in Option A. Exclude bats by covering the one existing entry hole with a device that allows bats to exit the structure, but prevents them from reentering (see Figs. 6–10). Install the exclusion devices during the day and leave them in place for five to seven days (longer during particularly cool or rainy weather).

When bats are using multiple openings to exit and enter, exclusion devices should be placed on each opening, unless you can be sure that all roosting areas used by the bats are connected. If all the roosting areas are connected, all but one or two exit holes can be sealed as described below. Place exclusion devices over the one or two remaining exit holes.

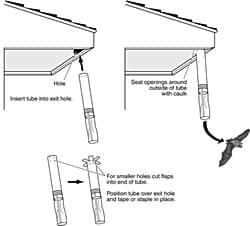

Figure 6: Drawing Credit - BCI

If the colony contains a hundred bats or more, which is common, leaving only one exit point can create a bat "log jam." In this case, some bats might look for alternative ways out of the roost area, finding their way into human-occupied areas. It is important to make sure bats are able to exit freely. If they do not appear to be exiting, or appear to be having trouble doing so, open additional exits.

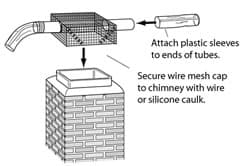

After all bats have been excluded, remove the exclusion devices and immediately seal up the exits to prevent bats from reentering. If necessary, install a chimney cover, available from home improvement centers.

A one-way door (Fig. 6) allows bats to exit a structure, but prevents them from reentering. Hang a sheet of construction grade plastic, screen-door material, or lightweight polypropylene netting (half-inch mesh) over the exit. Use staples or duct tape to attach the material to the building. The one-way door should extend 18 to 24 inches below the bottom edge of the opening. Leave the material loose enough to flop back after each bat exits.

Figure 7: Drawing Credit - BCI

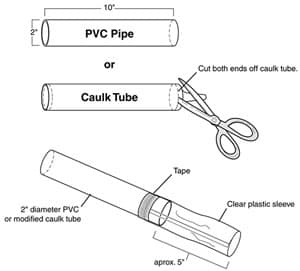

One-way tubes (Fig. 7) work where one-way doors won't, such as on horizontal surfaces. A flexible pipe or cardboard tube is easy to fit into a crevice or cut to create flaps that can be fit over an opening and be stapled, nailed, or taped to a building. Do not let the tube project more than a quarter-inch into the opening to make sure that bats can easily enter the tube.

One-way tubes should be at least two inches in diameter, 10 inches in length, and have a smooth interior so bats are unable to cling to the inside (Fig. 8). One-way tubes can be made from PVC pipe, flexible plastic tubing, empty caulking tubes, or dryer vent hose (Fig. 9). To reduce the likelihood of bats reentering, a piece of plastic sheeting can be taped around the exit end of the tube.

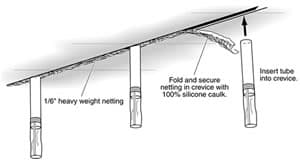

Some areas have lengthy crevices used by bats. Multiple exclusion tubes will need to be placed every few feet along the length of each crevice; spaces between the tubes should be closed with heavyweight netting or other material. The same procedure can be used in lengthy crevices created where flashing has pulled away from a wall.

One-way Tubes for Chimneys:

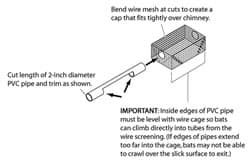

- If bats are roosting inside a chimney, construct a wire cage from quarter-inch mesh hardware cloth (Fig. 10a).

- Cut holes in the sides of the wire cage and insert a modified section of two-inch PVC pipe (Fig. 10b).

- To further reduce the likelihood of bats reentering, tape a piece of plastic sheeting around the exit ends of the tube (Fig. 10c).

Bats Roosting Above Porches and Other Areas

Bats temporarily roost above porches or under overhangs at night to eat large prey, digest, rest, and socialize. In such cases, they may frighten humans or their droppings may accumulate.

Mylar balloons or strips of aluminum foil hung from the porch ceiling and allowed to move in the breeze may discourage bats from roosting in the area. Nontoxic aerosol sprays, designed to repel dogs and cats, can prevent bats from night-roosting in these areas; apply the spray by day when bats are not present. This treatment is reported to be effective for up to several months. (Aerosol repellents are not an adequate substitute for excluding bats that are using the area as a day roost, and should never be applied when bats are in a roost)

Public Health Concerns

Histoplasmosis

Large accumulations of bat droppings may harbor histoplasmosis fungi spores, which when inhaled can result in a lung infection referred to as "histo." No histo cases have been reported in Maine, but precautions should be followed when cleaning or removing large accumulations of bat droppings. Call your local health department for recommendations.

Rabies

People are more often concerned about bats because of rabies, a virus that affects the nervous system of humans and all other mammals. If you do not handle bats, your odds of contracting rabies are extremely small.

Rabies is spread when the saliva of an infected animal enters the body through a bite or scratch, or makes contact with the eyes, nose, mouth, or break in the skin. There is little risk of contracting rabies from a bat as long as you exercise caution. People cannot get rabies from touching bat droppings, blood, urine, or fur.

Five to ten percent of bats that the Maine State Department of Health tests have rabies. The department estimates, however, that probably less than one percent of the native wild bat population has the disease.

If a bat does contract rabies, it is unlikely to be a threat as long as people follow simple precautions. Most bats infected with rabies become paralyzed and fall to the ground. If you pick up a sick bat – and it bites you in self-defense – you risk contracting the disease. If you refrain from picking up a (sick) bat, you avoid exposing yourself.

Note: Young bats also fall to the ground when learning to fly. They may also have hit a window and been stunned, or simply be cold and unable to fly.

If you think you have been bitten, scratched, or exposed to rabies via a bat:

- Thoroughly wash with soap and water a wound or other area that came into contact with the bat.

- Capture or isolate the bat, if you can, without risking further contact. (See "Bat Encounters Inside or Outside Your Home" for safe capture techniques)

- Call your doctor or local health department for an evaluation of the potential of rabies exposure and the need for follow-up treatment. People usually know when a bat has bitten them, but because bats have small teeth and claws, the marks may be difficult to see. You can also make arrangements to have the bat tested for rabies, if necessary.

- In the following situations – even in the absence of an obvious bite or scratch – contact your local health department or your doctor and get the bat tested:

- A bat is found in a room with a sleeping person

- A bat is found in a room with an unattended child

- A bat is found near a child outside

- A bat is found in a room with a person who is under the influence of alcohol or drugs, or who has another sensory or mental impairment.

What About Rabies and Your Pet?

In Maine, the law requires pet owners to vaccinate their dogs yearly and their cats every other year. All cats, even indoor cats, should be vaccinated for rabies.

Each year, the National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians publishes guidelines that unequivocally state if an unvaccinated animal comes in contact with a potentially rabid animal, and the potentially rabid animal cannot be tested, then the unvaccinated animal should be either euthanized or be held in strict quarantine for six months.

As few people are willing to do either, the message is clear: Vaccinate your pets!

Bat Encounters Inside or Outside Your Home

In spring and fall, migrating bats may temporarily roost outside on window screens, fence posts, piles of lumber, and other unlikely places. If a bat is seen roosting outside during daylight hours, leave it alone. It will probably be gone the following morning.

If a bat flies into your home it's probably a juvenile learning to fly, a solitary male following prey, or an adult that has been excluded from its roost. Bats often enter through an open door or window, or by coming down a chimney into an unused fireplace. If a bat is found inside during the day, confine it to one room. Place a towel under doors to prevent the bat from moving into other parts of the house. Leave the area alone until nightfall.

At nightfall (if you are sure the bat has not been in contact with humans or pets), turn off any lights in the room where the bat is confined, open all doors and windows that lead outside, and stand in the corner. This allows you to watch the bat while staying out of its way (If you must move around the room, stay as near to the wall as possible). Be prepared to watch the bat for up to 20 minutes. Normally, the bat will fly around the room to orient itself and then leave.

If the bat seems to have disappeared but you haven't seen it leave, it may be perched somewhere, such as behind a curtain, in hanging clothes, or in a houseplant. The bat will generally choose a high place to roost. Moving these things around with a broomstick may arouse the bat. If the bat doesn't leave, it can be caught and removed.

Figure 11: Drawing Credit - BCI

Approach the bat slowly (Fig. 11) and place a container such as a small box, large glass, plastic bowl, or coffee can over it. Next, gently slide a piece of cereal box paper or cardboard underneath the bat (be gentle—bats are fragile animals). Using the paper as a cover, take the bat outside and release it away from people and pets. The ideal method is to place the container against a tree, slowly slide the paper away, and then remove the container. Releasing the bat against a tree allows the bat to rest safe from potential predators.

You may also use leather gloves and a pillowcase (Never handle a bat with your bare hands). Put your gloved hand inside the pillowcase and gently place the cloth over the bat. Then fold the pillowcase over the bat so it is inside. Take the bat outdoors and safely release it on a rough tree trunk or lightly shake the pillowcase until the bat flies off. In the absence of a container or pillowcase and gloves, use a thick towel. Roll the bat up gently and release it outside.

Note: State wildlife offices do not provide bat removal services, but they can provide names of individuals or companies that do. To find such help yourself, look up "Animal Control," "Wildlife Control," or "Pest Control" in your phone directory. Bats can be caught and released outdoors away from people and pets.

Legal Status

Many Maine bat species are protected under the Endangered Species Act; for more specific information, contact your regional wildlife office. In addition, all species of bats are classified as protected wildlife and cannot be hunted, trapped, or killed. The Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife makes exceptions for bats found in or immediately adjacent to a dwelling or other occupied building. In such cases, no permit is needed to legally remove the animals.

Additional Information

Books

Landscaping for Wildlife in the Pacific Northwest

Written by: Russell Link

Seattle: University of Washington Press and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, 1999.

Living with Wildlife in the Pacific Northwest

Written by: Russell Link

Seattle: University of Washington Press and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, 2004.

Stokes Beginner's Guide to Bats

Written by: Kim Williams, Rob Mies, Donald Stokes, and Lillian Stokes

Little, Brown and Company, 2002.

The Bat House Builder's Book

Written by: Merlin D. Tuttle, and Donna L. Hensley

Austin, TX: Bat Conservation International, 1995; University of Texas Press, 2001.

Organizations and Internet Resources

Adapted from "Living with Wildlife in the Pacific Northwest"

Written by: Russell Link, Urban Wildlife Biologist

Photos and Illustrations: As credited

Copyright 2004 by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife