DACF Home → Bureaus & Programs → Maine Forest Service → About Us → Forest Health & Monitoring → Condition Reports → Issue 2: May 14, 2014

Forest & Shade Tree - Insect & Disease Conditions for Maine

Issue 2: May 14, 2014

- On this page:

In Memoriam: Douglas A. Stark

Douglas A. Stark, formerly a Forest Pathologist with the Maine Forest Service, passed away on April 18, 2014. Doug’s career with the Maine Forest Service spanned 32 years, from 1956 to 1988. His initial work here was focused on monitoring the spread of Dutch elm disease and on publicizing disease management protocols. Dutch elm disease was just starting to decimate the native elm populations in Maine’s cities, towns, and forests during the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, and Doug’s expertise was greatly appreciated by many town tree boards, municipalities, and private citizens. Doug was also a very passionate and well-respected authority on white pine blister rust. He was instrumental in advocating for the continuance of quarantine procedures for exclusion and removal of Ribes plants (currants and gooseberries), the primary hosts of the disease. These efforts have protected the valuable white pine resource in an economically efficient manner for the past several decades. The value of this work is especially appreciated now, as a new strain of the blister rust pathogen can now infect commercial cultivars of Ribes previously immune to the disease. A great deal of his time was also spent on spruce budworm management and control operations during the large epidemic of the 1970’s. Doug was heavily involved in chestnut restoration efforts in Maine, locating residual survivors on the landscape and working with others on the restoration efforts which are now coming to fruition. Doug is remembered as a wonderful teacher and mentor, an expert tree disease diagnostician, and a meticulous recorder of field observations of tree and forest health and general forest conditions. He always presented a courteous and professional manner to clientele and co-worker alike, and was a friend we shall all miss.

Douglas A. Stark, formerly a Forest Pathologist with the Maine Forest Service, passed away on April 18, 2014. Doug’s career with the Maine Forest Service spanned 32 years, from 1956 to 1988. His initial work here was focused on monitoring the spread of Dutch elm disease and on publicizing disease management protocols. Dutch elm disease was just starting to decimate the native elm populations in Maine’s cities, towns, and forests during the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, and Doug’s expertise was greatly appreciated by many town tree boards, municipalities, and private citizens. Doug was also a very passionate and well-respected authority on white pine blister rust. He was instrumental in advocating for the continuance of quarantine procedures for exclusion and removal of Ribes plants (currants and gooseberries), the primary hosts of the disease. These efforts have protected the valuable white pine resource in an economically efficient manner for the past several decades. The value of this work is especially appreciated now, as a new strain of the blister rust pathogen can now infect commercial cultivars of Ribes previously immune to the disease. A great deal of his time was also spent on spruce budworm management and control operations during the large epidemic of the 1970’s. Doug was heavily involved in chestnut restoration efforts in Maine, locating residual survivors on the landscape and working with others on the restoration efforts which are now coming to fruition. Doug is remembered as a wonderful teacher and mentor, an expert tree disease diagnostician, and a meticulous recorder of field observations of tree and forest health and general forest conditions. He always presented a courteous and professional manner to clientele and co-worker alike, and was a friend we shall all miss.

Arbor Week—Ash Tree Tagging Update

This year Arbor Week coincides with Emerald Ash Borer Awareness Week: May 18-24, 2014. Maine’s Project Canopy and Forest Pest Outreach Program are encouraging people around the state to include an ash tree tagging event as part of their community celebrations of trees during the week. To date the communities of Bath, Farmington, Kennebunkport, Portland and Yarmouth are participating in Ash Tree Tagging. If you are interested in participating in this program, or want more information about Arbor Week in Maine, contact Jan Santerre at 207-287-4987 or jan.santerre@maine.gov.

Staff Additions

Introductions to Josie Lahey, Patti Roberts and Julie Churchill are overdue.

Josie joined our group in January and graduated from USM last weekend! She has been working nearly full time here, while finishing up a chemistry class at the university. Josie fills the position left vacant when Bill Urquhart passed away last July. She has taken several entomology-themed courses while at USM, as well as worked on a sawfly project under Dr. Joseph Staples and volunteered at the Maine Medical Center Research Institute Vector Borne Disease Lab working with everyone’s favorite disease vectors (ticks and mosquitoes). Josie has been working on browntail moth, emerald ash borer, the insect collection and website projects.

Patti fills the position left vacant when Jean Maheux retired in December 2011. Jean had already left her desk at 50 Hospital Street years before retirement and had been working out of the Maine Forest Service office in Harlow. Patti brings an office assistant’s presence back to the lab at least one day a week—if you’d like to welcome her as part of your insect or disease inquiry, call on a Monday! Patti has taken everything we’ve thrown at her in stride—storing her lunch alongside entomology and pathology samples in the fridge, gamely counting the carpenter ants she squashes (even those bold enough to venture across her desk), handling contracts (and negotiating for us), and properly stowing browntail moth webs and pole pruners. We’re impressed by her enthusiasm, and think you will be too.

Julie is returning for a second summer, but 2013 being what it was, was not introduced last year. She will be assisting with insect and disease survey this summer. Last year she primarily worked on emerald ash borer detection surveys, and spent some time assisting the forest inventory program as well. Julie is a forestry student at the University of Maine in Orono.

Insects

Browntail Moth (Euproctis chrysorrhoea) – Browntail moth populations are starting to rise again in parts of Topsham, Bowdoinham, Bath and West Bath (Sagadahoc County) and Brunswick and Freeport (Cumberland County). Isolated populations of these insects can be found scattered throughout the midcoast and inland to Turner (Androscoggin County) and Vassalboro (Kennebec County).

The larvae have been active since the end of April and can be found feeding on newly emerging foliage.

The larvae have been active since the end of April and can be found feeding on newly emerging foliage.

Browntail moth larvae feed on the emerging foliage of oak, apple, birch, cherry, hawthorn, rose and other hardwoods. They emerge from their overwintering webs starting the end of April, even before the buds have broken. They continue to feed on leaves and molt their hairy skins through June when they pupate leaving their last hairy skin behind. Besides defoliating trees and causing branch dieback and tree mortality, all those hairs make many people itch.

Pruning out webs and destroying them (drop them in soapy water) may eliminate the problem if all the webs are within reach. Clipping should be completed by the end of April and insecticide applications (if warranted) should be made during the month of May by a registered pesticide applicator. There are specific regulations for controlling browntail moth near coastal waters. Be sure to check on the current Board of Pesticide Control regulations before treatment.

Christmas Tree Pests – The season to treat for balsam twig aphid is upon us in southern Maine. In far Northern Maine you may still have time to treat for balsam shootboring sawfly, but that window will soon close. If you have damaging levels of balsam gall midge, you need to monitor your fir for appropriate development to time treatment of the pest. For some growers treatments will need to occur before the first of June. See the May Guide for Pest Management below for more information.

If you’ll be using Diazinon AG500 or AG600 for management of Christmas tree pests, be sure to have the supplemental labels on hand. If you plan to use Diazinon 50W, the balsam fir use in Maine has been written in to the new Section 3 label. You can find the labels at the links below, or if you need a hard copy you can contact us.

DIAZINON AG500, EPA Reg. No. 66222-9, SUPPLEMENTAL DIRECTIONS FOR USE ON BALSAM FIR IN MAINE ONLY, http://www.maine.gov/dacf/mfs/forest_health/documents/66222-9DiazinonAG500MESupplabelissued10-11-11.pdf

DIAZINON AG600, EPA Reg. No. 66222-103-34704, SUPPLEMENTAL LABELING FOR INSECT CONTROL ON ORNAMENTALS GROWN OUTDOORS IN NURSERIES: BALSAM FIR/MAINE ONLY, http://www.maine.gov/dacf/mfs/forest_health/documents/66222-103-34704DiazinonAG600WBCSupplementalLabelforBalsamFirinMaineOnly.pdf

DIAZINON 50W, EPA Reg. No. 66222-10. SECTION 3 LABEL

Emerald Ash Borer(Agrilus planipennis) – All 34 girdled trap trees last year were negative for signs of emerald ash borer (EAB). We are starting to girdle trees again this year to continue monitoring for EAB. If you have an ash tree of any species over four inches DBH that you would be willing to sacrifice as a trap tree, please email Colleen Teerling at colleen.teerling@maine.gov. We are also placing over 600 purple traps throughout the state this year to monitor for EAB. As always, remember to watch for ‘blonding’: woodpecker feeding on ash trees that might indicate the presence of EAB.

Ground-Nesting Bees – This is the time of year when solitary ground-dwelling bees emerge and become active. When they first emerge they are usually very active, with much flying around, mating, exploration and nest-building. All this activity by bees can look rather frightening. However solitary bees (one nest for each female, although you may have many nests in one area) are generally non-aggressive and must be severely harassed before they sting. The males often look aggressive while they fly around searching for a mate, but they can’t sting at all. This heightened activity persists for only a week or two, and then the bees are almost unnoticeable. Ground nesting bees are valuable pollinators.

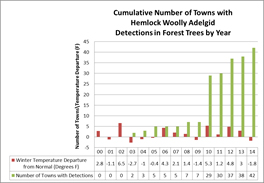

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid(Adelges tsugae) – Detections of hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA) continue to march inland and eastward. UNH graduate student/USDA Forest Service intern Justin Williams successfully found HWA in Lebanon and Sanford (York County) using remote sensing to identify stressed hemlock. Ground checks revealed low-level infestations at the two identified sites. Adelgid was also found in Friendship and Owls Head (Knox County) during Maine Forest Service detection surveys. For those of you keeping track, that brings us to 42 towns in 5 counties with HWA detections in the forest since the first forest detection 10.75 years ago (see chart).

The detection in Owls Head was adjacent to a 2002 Sasajiscymnus tsugae beetle release on balsam woolly adelgid. Sampling of hemlock woolly adelgid infested trees did not result in beetle recoveries. This is expected.

The detection in Owls Head was adjacent to a 2002 Sasajiscymnus tsugae beetle release on balsam woolly adelgid. Sampling of hemlock woolly adelgid infested trees did not result in beetle recoveries. This is expected.

HWA development has been delayed by the cool spring. Eggs were not present during a mid-April check in Harpswell (Cumberland County), but oviposition had begun by late-April.

Trees in Harpswell have shown a rapid progression of infestation (from undetectable to “plastered” in a couple of years). Some of the most severe decline also has been observed in this area as well as on other coastal peninsulas and islands. These locations seem to have a combination of climate and soils (or lack thereof) that contributes to a more rapid buildup of the insect and decline of the host than has been observed in southern York County.

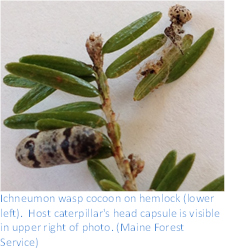

Ichneumon Wasp Cocoon – A hemlock sample collected due to scale concerns revealed no scale—the suspect marks were wounds in the needle tissue—but did have a beautiful reminder of the many insects working in beneficial roles in our forests. Eisman and Charney, in Tracks and Signs of Insects and other Invertebrates (2010), identify these “Easter egg” cocoons as structures created by ichneumon wasps in the Campopleginae subfamily. If you’re like me, once you see a picture of one, you’ll notice them everywhere you go in the woods.

Ichneumon Wasp Cocoon – A hemlock sample collected due to scale concerns revealed no scale—the suspect marks were wounds in the needle tissue—but did have a beautiful reminder of the many insects working in beneficial roles in our forests. Eisman and Charney, in Tracks and Signs of Insects and other Invertebrates (2010), identify these “Easter egg” cocoons as structures created by ichneumon wasps in the Campopleginae subfamily. If you’re like me, once you see a picture of one, you’ll notice them everywhere you go in the woods.

Most wasps in this group are parasites of caterpillars. This is the case of the one submitted on the hemlock sample, the head capsule of the host, visible in the photo, was clearly “caterpillar.” To see a nice summary of the subfamily and a reminder of the specialized languages of biology visit the bugguide page: http://bugguide.net/node/view/21674.

The sample is hanging on my bulletin board. Maybe someday it will produce an adult wasp. However, it may not be the same species as spun the cocoon (see Eisman’s blog post from 2012 to find out more: http://bugtracks.wordpress.com/2012/02/13/campoplegines-part-1/).

Oak Gall Wasps – As we wrapped up writing of the last issue of the Conditions Report one of our subscribers walked in with a sample of gouty oak gall caused by Callirhytis quercuspunctata. The authors of the USFS oak pest guide count this among more than 600 insects that cause galls on oaks in the United States!

Oak Gall Wasps – As we wrapped up writing of the last issue of the Conditions Report one of our subscribers walked in with a sample of gouty oak gall caused by Callirhytis quercuspunctata. The authors of the USFS oak pest guide count this among more than 600 insects that cause galls on oaks in the United States!

Most oak gall wasps do not cause significant damage to their host tree. C. quercuspunctata is among the exceptions. In some cases it can have a significant impact even contributing to tree mortality. Usually damage is light and with significant damage, effective controls are not available. Management can include pruning affected twigs before adult wasp emergence and removing heavily impacted hosts. Natural controls include other insects and, as is evident in the photo, larger animals as well.

In eastern Massachusetts forest health workers, entomologists, arborists and others are puzzling over the outbreak of a cynipid gall wasp, causing widespread defoliation and branch dieback as well as some tree mortality. Although this has been tentatively identified as the same species that caused oak decline in Long Island in the 1990’s, the crypt gall wasp (Bassettia ceropteroides), so little is known of the group that this identity is not certain. However, this is certainly a wasp (whatever its name is!) to be on the lookout for in Maine’s coastal oaks.

Six Spotted Tiger Beetles (Cicindela sexguttata) –In southern Maine tiger beetle adults are becoming active. Their brilliant green coloration fools even those educated about EAB. A closer look, however and people notice the body shape is off (blockier with a “neck” and “head” visible), their legs are too long, and “Holy Cow!” look at the size of those jaws!

The folks at Fairfax County Virginia Public Schools point out another key feature of the tiger beetle that can help you discriminate between it and EAB, “Adult beetles are fast runners and fliers. When they fly, they usually stay within three feet of the ground.” You would not expect to find EAB adults consistently hanging out at ground level—or running very much.

Spruce Beetle(Dendroctonus rufipennis) – Spruce beetle was reported from Sanford (York County) in ornamental Colorado blue spruce. A site visit was not made, but it is assumed that the trees had been subject to severe defoliation by Rhizosphaera needlecast. The severe impact of years of needlecast disease on landscape blue spruce, large and small, is visible throughout Maine. Consider removing large declining trees which are fodder for spruce beetle and other secondary organisms.

Winter Moth(Operophtera brumata) – Winter moth larvae started emerging the last week of April and are feeding on oak, apple, maple, birch, blueberry and other deciduous trees and shrubs. As of this week larval counts in Harpswell, Cape Elizabeth, Kittery and South Portland indicate that the December snow and cold apparently did not reduce the populations significantly over last year. This, despite the fact that there was only one large moth flight night in 2013 versus nine nights in 2012. Expect heavy defoliation in areas that were hit by winter moth last year and more damage in surrounding areas as well: along the coast from Kittery to Rockland.

Winter Moth(Operophtera brumata) – Winter moth larvae started emerging the last week of April and are feeding on oak, apple, maple, birch, blueberry and other deciduous trees and shrubs. As of this week larval counts in Harpswell, Cape Elizabeth, Kittery and South Portland indicate that the December snow and cold apparently did not reduce the populations significantly over last year. This, despite the fact that there was only one large moth flight night in 2013 versus nine nights in 2012. Expect heavy defoliation in areas that were hit by winter moth last year and more damage in surrounding areas as well: along the coast from Kittery to Rockland.

Winter moth larvae are small green inchworms that hatch in early spring and initially put out silk to ‘balloon’ on the wind dispersing to more hosts. They then feed first on the buds, webbing the new leaves together. As the leaves expand the feeding damage takes on the appearance of Swiss cheese and then the larvae consume all the foliage as the infestation progresses. Larvae will move to other hosts as they consume all the foliage on a tree. Feeding is completed in early June when the larvae ‘silk down’ to the ground where they form cocoons and stay all summer and fall. The adults emerge from the ground in late November and December.

The Maine Forest Service will be releasing the parasitic flies, Cyzenis albicans, for a second year in conjunction with the University of Massachusetts and funded by the USDA.

The first question people always ask about this biocontrol is, “Will the flies bother anything else (like people)?” The answer is no. This species was released in Nova Scotia in the 1960’s, brought the winter moth population under control and there have been no adverse effects in the intervening 50 years. Flies were also released in British Columbia, again with no impacts on other insects or people. The flies are very closely tied to the winter moth life cycle and need winter moth to survive. There will always be some winter moth around now that they have become established in Maine, but hopefully the flies, once established, will do their job and bring the winter moth population under control in a few years.

It will be years before we see the results of the biocontrol effort as it takes time for the flies to become acclimated to a new location and build up their population to a high enough level that it will have a noticeable impact on the winter moth population. In the meantime people will see defoliation on hardwood trees and shrubs in May. With luck this will not have an adverse effect on the trees before the parasite population catches up to the winter moth population and brings them into balance in Maine.

Critical Information:

A concern is spreading the winter moth further. Larvae disperse to some extent by ballooning to nearby locations. But humans are probably a far greater factor in moving this insect than natural spread. Winter moth cocoons are in the soil from late May until November. Any landscape plants moved from infested areas can have winter moth in the soil. Don’t move plants from areas infested with winter moth. This includes tree saplings that are dug in the spring as they will have eggs and/or larvae on them.

Please report any hardwood defoliation this spring so that we can check out which insect is feeding on the trees. Winter moth particularly favor oak, but feed on a wide range of other hardwoods as well. The feeding makes leaves looks like Swiss cheese.

For more information go to: www.maine.gov/forestpests#wm.

Diseases and Injuries

Hardwood Anthracnose Diseases - The period between mid-May and early June is the most effective time to apply protectant fungicides for the prevention of anthracnose diseases of hardwoods. Anthracnose diseases cause irregular tan or brown spots or blotches on leaves, sometimes followed by curling and cupping of severely affected leaves and premature defoliation. Disease occurrence and severity varies from year to year, and is largely driven by extended periods of wet weather, including rain, fog, or even extended cloudy periods where foliage does not have the opportunity to dry. Maples, ashes, and especially oaks have been affected in recent past years. Although anthracnose diseases rarely result in long-term damage, if ornamental trees have been severely affected for several consecutive years fungicide protection is a reasonable consideration to preserve tree health. There is a wide variety of trade names for recommended fungicides for anthracnose diseases. Most available materials contain one of the following active ingredients: chlorothalonil, copper (copper sulfate), manganese or zinc.

Spruce Needlecast (Rhizosphaera kalkhoffii) - Spruce needlecast continues to cause widespread and serious injury to white and Colorado blue spruces throughout the state. Prolonged infections have resulted in severe dieback and mortality in ornamental and roadside plantings. Applications of protectant fungicides (chlorothalonil or copper-based) to current-season needles will protect the new foliage, but will not help needles already infected. Fungicides need to be applied just after budbreak ( after the new buds lose the protective bud scale sheath in late May or early June), and again about two weeks later, when the needles are nearly full-grown.

White Pine Blister Rust (Cronartium ribicola) - Branch and stem infections on eastern white pine caused by the pathogen Cronartium ribicola are now producing the “blister” stage of the disease. Orange to orange-yellow or cream-colored spore masses are easy to detect at this time of year. Pruning infected branches can prevent the fungus from reaching the main stem and killing infected trees. The removal of branch cankers is especially effective on younger, sapling-sized trees. Active cankers on the main stem are very difficult to contain, and nearly always result in tree mortality.

The pathogen alternates its life stages between species of Ribes (currants and gooseberries) and eastern white pine. The spores (aeciospores) being produced on the pine in spring can only infect leaves of Ribes spp. Native Ribes species should be removed from within 900 to 1000 feet of white pine plantations or stands to provide protection from infection. Introduced and commercially-grown species of Ribes are prohibited throughout the state by white quarantine regulations. For more specific information on the quarantine, please refer to: http://www.maine.gov/dacf/mfs/forest_health/quarantine_information.html#wpbr.

White Pine Needle Diseases - For the past several years, white pines have been affected by several needle disease fungi that result in heavy shedding of one-year-old needles during the month of June (see http://na.fs.fed.us/pubs/palerts/white_pine/eastern_white_pine.pdf ). Last year, the spring and early summer months again saw above-average rainfall, with extended wet periods, conditions which are highly favorable to needle infection. The probability for significant needle loss this year therefore, remains very high.

Because this disease complex and the severity with which it is progressing appears to be a relatively new phenomenon to the New England states, management options for affected forest stands have not yet been tested. However, the current recommendation remains to exercise extreme caution when prescribing or conducting thinning operations. Thinning may help to improve air-flow and drying of the foliage, and thereby reduce needle infection in relatively healthy stands. Thinning in stands that have been stressed (with heavy needle loss or from other factors) for several consecutive years will be a significant health risk. Similarly, stands with pines showing a “tufted” appearance of branch foliage, or showing recent branch shedding and loss of lower limbs are stands low in vigor. In these stands, thinning is likely to be an increased stress and could result in further stand decline and residual tree mortality.

Winter Injury - Numerous cases of winter injury on Rhododendrons have been sent to the Lab in the past few weeks. Winter injury can be caused by any one of three general conditions; foliage desiccation, rapid temperature drops and low temperatures over an extended period of time. The temperatures through the winter season were lower than normal. However, in most areas they did not reach the extreme lows nor did rapid temperature drops occur which would result in severe winter injury. Rather, it was likely the extended periods of low temperatures that caused the extensive winter damage. Also observed was a wide variation in the response of particular individuals, with some plants heavily damaged while neighboring plants were left relatively untouched. Much of this variation is attributed to the specific cultivars (refer to the Univ. Vermont study at http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/JARS/v38n2/v38n2-pellett.htm).

Winter Injury - Numerous cases of winter injury on Rhododendrons have been sent to the Lab in the past few weeks. Winter injury can be caused by any one of three general conditions; foliage desiccation, rapid temperature drops and low temperatures over an extended period of time. The temperatures through the winter season were lower than normal. However, in most areas they did not reach the extreme lows nor did rapid temperature drops occur which would result in severe winter injury. Rather, it was likely the extended periods of low temperatures that caused the extensive winter damage. Also observed was a wide variation in the response of particular individuals, with some plants heavily damaged while neighboring plants were left relatively untouched. Much of this variation is attributed to the specific cultivars (refer to the Univ. Vermont study at http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/JARS/v38n2/v38n2-pellett.htm).

Several growers were concerned that the winter injury may have been infection by a serious root disease, Phytophthora ramorum. The symptoms may appear similar at first glance with leaves curling inwards, drying and dying. However, the dark staining in the woody stem tissue associated with P. ramorum infection will be absent in winter-killed stems. In addition, the symptoms of P. ramorum infection will likely first be noticed later during the growing season, and not in late winter and early spring. Finally, be aware that P. ramorum has not yet been established in Maine, even though some infected plant materials were discovered and eradicated from the state several years ago.

New Resource Now Available - UMass Extension's Professional Management Guide for Diseases of Trees and Shrubs has been freshly revised and updated for 2014, and is now available online. Most of the disease pathogens known to be pests of woody ornamentals in the Northeast region are covered in this guide. Included is host plant information, along with appropriate fungicides, bactericides, biological control materials, and cultural management information where applicable.

Go to http://extension.umass.edu/landscape/diseaseguide to access the Guide right now!

Guide to Pest Management in Maine—May 2014

The following table should assist you in the pest management planning process. Remember that this is just a guide and that conditions will vary. Many pests may be managed with several other suitable products not listed here, but also registered for use in Maine. This chart reflects those products that should be readily available and effective, but not to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. For more information on pests included in this guide, check for fact sheets on our website or call or write the Insect and Disease Laboratory, 168 State House Station, Augusta, Maine 04333-0168, Phone (207) 287-2431, Fax (207) 287-2432.

| Insect or Disease | Cultural Controls | Chemical Controls |

|---|---|---|

|

The tiny mosquito-like adults should emerge between now and early June. Christmas tree growers should monitor their plantations and apply Diazinon** or chlorpyrifos (Lorsban**) if needed as the new needles emerge and flatten. |

|

|

Too late now for chemical control. |

|

|

Control with Diazinon** or chlorpyrifos (Lorsban**) at bud break. Already past in southern Maine; still time in east and north. |

|

Rogue out and destroy infested stock from Christmas tree plantations and be sure that planting stock is from a clean source. In forested situations harvest ahead of mortality. |

Esfenvalerate (Asana XL**) or imidacloprid (Merit, Xytect). |

|

|

Watch for black fly-like adults around the foliage from now through mid-June. Apply foliar treatment with carbaryl (Sevin) or acephate (Orthene) when small developing mines (seen as small translucent spots in the leaves) are evident. |

|

Avoid mowing or raking in infested areas to avoid stirring up the hazardous caterpillar hairs. Clip overwintering webs next winter. |

Treatment against the caterpillar stage should be done now. A list of applicators willing to treat browntail moth is available on our website or by request. Check with the Board of Pesticide Control for the regulations for spraying near water. |

|

Eggs have hatched in southern Maine. Tiny larvae frequently drift around on spring breezes. If found, be prepared to remove and destroy egg masses next fall. |

Bt (Dipel or Thuricide), Acephate (Orthene), carbaryl (Sevin), cyfluthrin (Tempo), or diflubenzuron (Dimilin**) when larvae are actively feeding (early June). |

|

|

Watch for tiny looper larvae with black heads in early June. Survey methods are available and should be done in early June for this season. Treat in late June if necessary with Bt. |

|

Please contact us. |

Please contact us. |

|

Remove and destroy infested leaves early as egg pouches or tiny larvae appear in late May. |

Treat older larvae with acephate (Orthene) or carbaryl (Sevin). |

|

Please contact us. |

Please contact us. |

|

Rhizosphaera Needlecast of Spruce |

|

Chlorothalonil (Bravo, Daconil), or copper sulfate (Bordeaux mix or Kocide) when new needles are +/- 0.5 inch long and again 10 days to two weeks later. |

Sphaeropsis (Diplodia) Tip Blight of 2 and 3 needle Pines |

|

Chlorothalonil (Bravo), copper sulfate (Kocide), or Thiophanate methyl (T-Methyl, Topsin) shortly after budbreak and again 10 days to two weeks later. |

Viburnum Leaf Beetle |

Prune off twigs with egg pockets on them before hatch (early- to mid-May). |

Treat infested shrubs early (before the end of May) with acephate (Orthene), carbaryl (Sevin) or imidacloprid (Merit, Xytect). |

Small infestations may be controlled by hand picking larvae and dropping them into soapy water. |

Watch for adults around foliage in late May and early June. Look for developing larvae in June and be prepared to treat with carbaryl (Sevin), imidacloprid (Merit), chlorpyrifos (Lorsban**) or spinosad (Success). |

|

Yellow Witches Broom of Balsam Fir |

Prune brooms from Christmas trees; make pruning cuts below galls at the bases of brooms. Weed control may help with management. Alternate hosts include chickweed and mouse-ear chickweed. |

None effective at this time. |

NOTE: These recommendations are not a substitute for pesticide labeling. Read the label before applying any pesticide. Pesticide recommendations are contingent on continued EPA and Maine Board of Pesticides Control registration and are subject to change.

Caution: For your own protection and that of the environment, apply the pesticide only in strict accordance with label directions and precautions.

**Restricted-use pesticide may be purchased and used only by certified applicators.

Conditions Report No. 2, 2014

On-line: http://www.maine.gov/dacf/mfs/publications/condition_reports.html

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE CONSERVATION & FORESTRY

Maine Forest Service - Forest Health and Monitoring

Contributors: Charlene Donahue, Allison Kanoti, William Ostrofsky, Jan Santerre (Forest Policy and Management), Colleen Teerling